Jesus, fellow traveller and friend,

you step out boldly on your journey,

chiding our fickleness and fear.

As you mark out the road ahead,

consecrate us as your companions,

so that we keep you in our sight

as our pattern and our guide.

Teach us to tread your paths of service,

granting us courage to follow you,

even to the foot of the cross,

to the place where, in pain,

the glory of your way is revealed.

Clare Amos

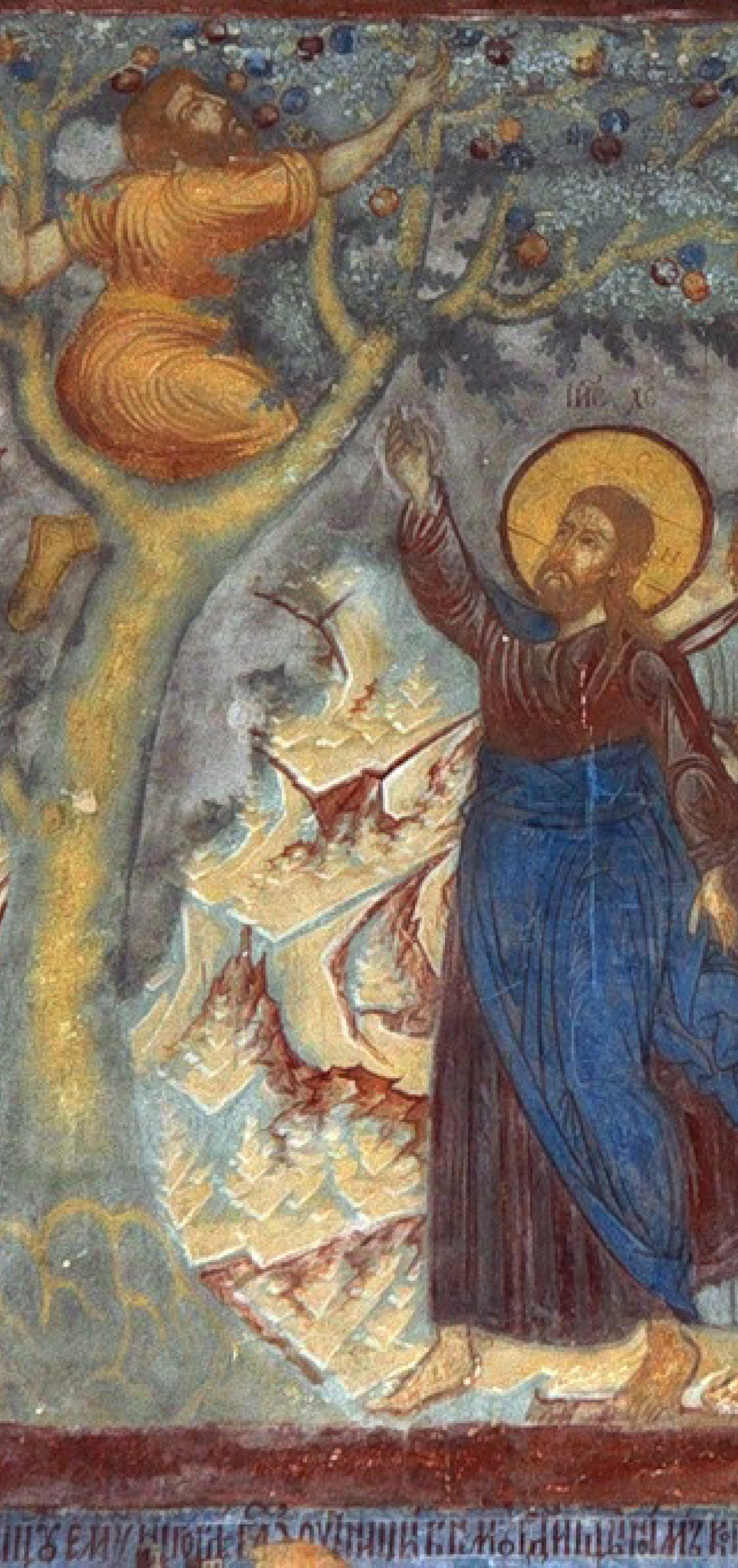

There’s an unmissable gear-change in the ninth chapter of Luke’s gospel. Jesus had just spoken with brutal clarity about his impending death. And then, he “set his face” towards Jerusalem (9.51), a phrase conveying that the path will be a hard and stony one, that bitter suffering lies at its end but also that those who tread it must be grittily determined, as unflinching as flint. The direction of travel is set. To the cross. But will his friends travel with him?

Tolkien fans may be reminded of Frodo Baggins, the little hobbit who sets out on an uncertain journey. “The Road goes ever on and on,” sings Frodo, “down from the door where it began. Now far ahead the Road has gone, and I must follow, if I can, pursuing it with eager feet, until it joins some larger way where many paths and errands meet. And whither then? I cannot say.”

Frodo’s friends, though given the chance to stay safely at home, “set their face” with his. Will we do so with Jesus? Clare Amos’ prayer asks him to “consecrate us as (his) companions”. It’s a brilliant line. As well as acknowledging our need for blessing as we set our faces with his towards Jerusalem, it reminds us of food offered for the journey. For “com-panions” are, literally, those who share bread together, and our “consecrated” bread is Jesus himself. Strengthened by him, we might make it “even to the foot of the cross”.

In Bach’s cantata Sehet, wir gehn hinauf gen Jerusalem we hear two voices who will not abandon Jesus. Their faces are set with his.